Jean-Marie Le Bris (1817 - 1872)

In 1856, two French naval officers accomplished brief though uncontrolled flight, Felix duTemple and Jean-Marie Le Bris who built a glider shaped like an albatross, a bird he had studied on his sea voyages. Charcoal of Le Bris by H. Schneider

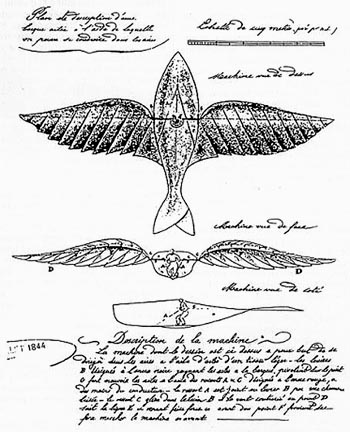

The body of the craft, which would support the pilot, was shaped like a canoe. Each narrow, arching wing was 23 feet (7 meters) long and adjustable by pulleys and cords. They provided a lifting surface of 215 square feet (20 square meters).

Le Bris : The Albatross, 1868 Download a 750pixel image Original Photo 1868 : M. Pépin

Le Bris tested his first aircraft in 1857 and successfully made a short glide on his first try, but a second attempt resulted in a crash and a broken leg. By 1868, Le Bris had developed a second, larger version of his glider, which made several successful manned test flights before it crashed and was destroyed.

Le Bris' Patent

1857 "...Le Bris's first experiment was conducted on a public road at Trefeuntec, near Douarnenez. Believing, like Count D' Esterno that it was necessary that the apparatus should have an initial velocity of its own, in addition to that of the wind, he chose a Sunday morning, when there was a good 10-knot breeze from the right direction, and setting his artificial albatross horizontally on a cart, he started down the road against the brisk wind, the cart being driven by a peasant. The bird, with extended wings, 50 ft. across, was held down by a rope passing under the rails of the cart and terminating in a slip knot fastened to Le Bris's wrist, so that with one jerk he could loosen the attachment and allow the rope to run. He stood upright in the canoe, unincumbered in his movements, his hands being on the levers and depressing the front edge of the wings, so that the wind should press upon the top only and hold them down, their position being, moreover, temporarily maintained by assistants walking along on each side." http://invention.psychology.msstate.edu

"...Once only did he obtain something like an ascension, by starting from a light wagon, which was not in motion. He was on the levee of the port of commerce at Brest, the breeze was light, and the gathered public was impatient, through failure to realize that success depended wholly on the intensity of the wind. Le Bris was hoping for a gust which should enable him to rise; he thought it had come, pulled on his levers, and thus threw his wings to the most favorable angle, but he only ascended a dozen yards, glided scarcely twice that distance, and after this brief demonstration came gently to the ground without any jerk." http://invention.psychology.msstate.edu

Le Bris Replica by M. Jenö Kiss Photo P. Dennez, Le Bourget, 1999 http://pdennez.free.fr/AVIONS/html/av739.html Download a 750pixel image

Further Reading

Progress in Flying Machines The writer of this record of "Progress in Flying Machines" originally hesitated whether he should include therein the account of the experiments of Captain [e Bris, which is about to follow. Not because he deemed it incredible in itself, nor because, if correctly stated, the experiments were not most interesting and instructive, but because the only account of them which he had been able to procure was contained in a novel, in which the author, to make the book more attractive, had mixed up a love story with the record of the aerial experiments, which combination, in the present state of disbelief, the writer feared might be too much for the credulity of the reader. It is true that the author of the novel23 said that the account of the experiments was scrupulously correct, and that in this, the principal object of the book, he had endeavored to he very exact, even at the risk of detracting from his hero. It is also a fact that the Aéronaute24 in reviewing the book, said:

Throughout the novel are to be found absolutely historical data concerning the artificial bird of Le Bris his experiments, his partial success, his mischances, and his deplorable final failure, the latter not through a radical defect, but through lack of method, steadiness in thought, and attention to details.But still the writer hesitated to reproduce this tale of an ancient mariner. Fortunately, after a year's seeking, he succeeded in getting a copy of an historical book, now quite out of print, by the same author,25 which gives without any embellishments an account of Captain Le Bris's experiments, and quite confirms that given in the novel, wherein it is said to have been related " with scrupulous exactness." From the historical work, therefore, of M. de la Landelle, supplemented by his novel, the following account has been compiled of what seems to have been a very remarkable series of experiments on "aspiration." Captain Le Bris was a French mariner, who had in his younger days made several voyages around the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn, and whose imagination had been fired by the sight of the albatross, sporting in the tempest on rigid wings, and keeping up with the fleetest ships without exertion. He had killed one of these birds, and claimed to have observed a very remarkable phenomenon. In his own words, as quoted by M. de la Landelle:

I took the wing of the albatross and exposed it to the breeze; and lo ! in spite of me it drew forward into the wind; notwithstanding my resistance it tended to rise. Thus I had discovered the secret of the bird ! I comprehended the whole mystery of flight.Possessed with an ardent imagination, he early became smitten with the design of building an artificial bird capable of carrying him, whose wings should be controlled by means of levers and by a system of rigging; and when he returned to France, and had become the captain of a coasting vessel, sailing from Douarnenez (Finistère), where he was born, and where he had married, he designed and constructed with his own hands the artificial albatross This consisted of a body in the shape of a "sabot," or wooden shoe, the front portion being decked over, provided with two flexible wings and a tail. The body was built like a canoe, being 13 1/2 ft. Iong and 4 ft. wide at its broadest point, made of light ash ribs well stayed, and covered on the outside with impermeable cloth, so it could float. A small inclined mast in front supported the pulleys and cords intended to work the wings. The latter were each 23 ft. long, so that the apparatus was 50 ft. across, and spread about 215 sq. ft. of supporting surface; the total weight, without the operator, being 92 Ibs. The tail was hinged so as to steer both up and down and sideways, the whole apparatus being, as near as might be, proportioned like the albatross. The front edge of the wings was made of a flexible piece of wood, shaped like the front edge of the wing of the albatross, and to this, cross wands were fastened and covered with canton flannel, the flocculent side down. An ingenious arrangement, which Le Bris called his rotules (knee pans), worked by two powerful levers, imparted a rotary motion to the front edge of the wings, and also permitted of their adjustment to various angles of incidence with the wind. Le Bris was to stand upright in the canoe (an excellent position), his hands on the levers and cords, and his feet on a pedal to work the tail. His expectation was that, with a strong wind, he would rise into the air and reproduce all the evolutions of the soaring albatross, without any flapping whatever. Le Bris's first experiment was conducted on a public road at Trefeuntec, near Douarnenez. Believing, like Count D' Esterno that it was necessary that the apparatus should have an initial velocity of its own, in addition to that of the wind, he chose a Sunday morning, when there was a good 10-knot breeze from the right direction, and setting his artificial albatross horizontally on a cart, he started down the road against the brisk wind, the cart being driven by a peasant. The bird, with extended wings, 50 ft. across, was held down by a rope passing under the rails of the cart and terminating in a slip knot fastened to Le Bris's wrist, so that with one jerk he could loosen the attachment and allow the rope to run. He stood upright in the canoe, unincumbered in his movements, his hands being on the levers and depressing the front edge of the wings, so that the wind should press upon the top only and hold them down, their position being, moreover, temporarily maintained by assistants walking along on each side. When they came to the right turn in the road the assistants were directed to let go, and the driver was told to put his horse on a trot. Then Le Bris, pressing on his levers, slowly raised the front edge of the wings to a very slight angle of incidence; they fluttered a moment, and then took the wind like a sail on the under side, relieving the weight upon the cart so much that the horse began to gallop. With one jerk Le Bris loosened the fastening rope, but lo ! it did not run, and the bird did not rise. Instead of this, its ascending power counterbalanced the weight of the cart, and the horse galloped as if at full liberty. It was afterward ascertained that the running rope had been caught on a concealed nail, and that the apparatus had remained firmly fastened to the cart. Finally the rails of the latter gave way, the machine rose into the air, and Le Bris said he found himself perfectly balanced, going up steadily to a height of nearly 300 ft., and sailing about twice that distance over the road. But an accident had taken place. At the last moment the running rope had whipped and wound around the body of the driver, had lifted him from his seat, and carried him up into the air. He involuntarily performed the part of the tail of a kite; his weight, by an extraordinary chance, Just balancing the apparatus properly at the assumed angle of incidence, and with the strength of the brisk wind then blowing. Up above, in the machine, Le Bris felt himself well poised in the breeze, and exulted that he was about to pass two hours in the air; but below, the driver was hanging on to the rope and howling with fright and anguish. As soon as Le Bris became aware of this state of affairs, and this was doubtless in a very short time, he took measures to descend. He changed the angle of incidence of his wings, came down slowly, and manoeuvred so well that the driver gently reached the soil, entirely unharmed and ran off to catch his horse, who had stopped when he again felt the weight of the cart behind him; but the equilibrium of the artificial albatross was no longer the same, because part of the weight had been relieved, and Le Bris did not succeed in reascending. He managed with his levers to retard the descent, and came down entirely unhurt, but one wing struck the ground in advance of the other and was somewhat damaged. This exploit naturally caused a great deal of local talk. Captain Le Bris was considered a visionary crank by most persons, and as a hero by others. He was poor, and had to earn his daily bread, so that it was some little time before, with the aid of some friends, he repaired his machine and was ready to try it again. He determined this time to gain his initial velocity by dropping from a height, and for this purpose erected a mast, with a swinging yard, on the brink of a quarry, excavated in a sort of pocket, the bottom of which was well protected from the wind. In this quarry bottom he put his apparatus together, and standing in the canoe, it was suspended to a rope and hoisted up aloft to a height of some 30 ft. above the ridge, and nearly 100 ft. above the quarry bottom. A fresh breeze was blowing inland, and the yard was swung so that the apparatus should face both the wind and the quarry, while Le Bris adjusted his levers so that only the top surfaces of the wings should receive the wind. When he had, by trial, reached a proper balance, he raised upward the front edge of the wings, brought the tail into action through the pedal, and thought he felt himself well seated on the air, and, as it were, "aspired forward into the breeze." At this moment he tripped the hook suspending the apparatus, and the latter glided and sailed off toward the quarry. Scarcely had it reached the middle of the pocket, when it met a stratum of wind inclined at a different angle from that prevailing at the starting_point?a vertical eddy, so to speak?probably caused by the reaction of the wind against the sides of the quarry. The apparatus then tilted forward, Le Bris pressed on his levers to alter the plane of the wings, but he was not quick enough. The accounts of the bystanders were conflicting, but it was thought that the apparatus next oscillated upward, and then took a second downward dip, but in any event it finally pitched forward, and fell toward the bottom of the quarry. As soon as the apparatus became sheltered from the wind it righted up, and fell nearly vertically; but as it exposed rather less than 1 sq. ft. of surface to each pound of weight, it could scarcely act as a parachute, and it went down so violently that it was smashed all to pieces, and Le Bris, who at the last moment suspended himself to the mast of the canoe and sprang upward, nevertheless had a leg broken by the rebound of the levers. This accident practically ruined him, and put an end for 12 or 13 years to any further attempt to prove the soundness of his theory. He had failed in both experiments for want of adequate equilibrium. He fairly provided for the transverse balance by making his wings flexible, but the longitudinal equilibrium was defective, as he could not adjust the fore_and_aft balance as instantly as the circumstances changed. The bird does his like a flash by instinct; the man was compelled to reason it out, and he could not act quickly enough. M. de la Landelle makes the following comment:

He lacked the science of Dante (of Perugia), but he was ingenious, persevering, and the most intrepid of men. He was entirely in the right in locating himself upright, both arms and legs quite free, in an apparatus which was besides exceedingly well designed. None was better fitted than he to succeed in sailing flight (vol-à-voile) in imitation of his model, the albatross.In 1867 a public subscription at Brest enabled Le Bris to build a second artificial albatross, and this is the one represented by fig. 48. It was much like the first, but a trifle lighter, although a movable counterweight was added, intended to produce automatic equilibrium. The apparatus when completed was publicly exhibited, and attracted much attention; but the inventor no longer had the audacity of youth, and he was influenced by numberless contradictory counsellors. He wanted to proceed as at Douarnenez, by giving an initial velocity to his apparatus, but he was dissuaded from this. He was also urged to test his machine with ballast, instead of riding in it himself, which at once changed all the conditions of equilibrium, as there was no longer command over a varying angle of incidence, and yet a first mischance led him to resort to the method of experimenting without riding in the machine. M. de la Landelle relates the incident as follows:

Once only did he obtain something like an ascension, by starting from a light wagon, which was not in motion. He was on the levee of the port of commerce at Brest, the breeze was light, and the gathered public was impatient, through failure to realize that success depended wholly on the intensity of the wind. Le Bris was hoping for a gust which should enable him to rise; he thought it had come, pulled on his levers, and thus threw his wings to the most favorable angle, but he only ascended a dozen yards, glided scarcely twice that distance, and after this brief demonstration came gently to the ground without any jerk.This negative result occasioned a good many hostile comments, and so the inventor no longer experimented in public; but he had further bad luck; the machine was several times capsized at starting, and more or less injured, being repaired at the cost of Le Bris, whose means were nearly exhausted. Then he tried it in ballast with varying success, and on one occasion, the breeze being just right, it rose up some 50 yds., with a light line attached, and advanced against the wind as if gliding over it. Very soon the line became slack, and the assisting sailors were greatly astonished, for the bird, without waver, thus proceeded some 200 yds.; but at the approach of some rising ground, which undoubtedly altered the direction of the aerial current, the bird, shielded from the wind, began settling down, without jolt, very gently, and alighted so lightly that the grass was scarcely bruised. Encouraged by this partial success, Le Bris tried to reproduce the same results, but he met many mishaps, in which the apparatus was upset and injured. At last, one day, by a stiff northeast breeze, he installed his bird on top of the rising ground near which it had performed so well a few weeks before, and this time he meant to ride in the machine himself. He was dissuaded by his friends, and probably made a serious mistake in yielding to them, for the uncontrolled apparatus was not intended to adjust itself to a gusty wind. At any rate, the empty machine rose, but it did not sustain itself in the air. It gave a twist, a glide, and a plunge, and pitched forward to the ground, where it was shattered all to bits. The wings were broken, the covering cloth of the canoe was rent to pieces, while the bowsprit in front was broken and forced back like a dart into the canoe. The friends claimed that if the operator had been aboard, he surely would have been spitted and killed, but Le Bris maintained that if he had been aboard he could, with his levers, have changed the angle of the wings in time to avoid the wreck; he blamed himself for having surrendered his better judgment, and he gave way to profound despair. For this was the end. His second apparatus was smashed, his means and his credit were exhausted, his friends forsook him, and perhaps his own courage weakened, for he did not try again. He retired to his native place, where, after serving with honor in the war of 1870 he became a special constable, and was killed in 1872 by some ruffians whose enmity he had incurred. Le Bris had made a very earnest, and, upon the whole, a fairly intelligent effort to compass sailing flight by imitating the birds. He finally failed for want of sufficient pecuniary backing, and also, perhaps, for lack of scientific methods and knowledge, for even at that day Captain BÙlÙguic a French naval officer, had called attention to the importance of securing longitudinal equilibrium, the lack of which caused the failure of poor Le Bris. Had he secured this he might have succeeded far better, especially if he had adhered to his original conception as to the necessity for that initial velocity against the wind, which served him so well upon the first trial and so ill upon the second. Singularly enough, he does not seem in all his subsequent experiments to have sought to give his apparatus that forward motion of its own, which he, like Count D'Esterno, originally held to be indispensable. He had also proposed to carry on his experiments at sea, from a steam vessel under way, and whatever may have been the cause that made him give up this idea, it was a misfortune, for his apparatus was capable of floating, he was himself an excellent swimmer, and had he experimented from a vessel under motion, not only would he have been safe, but he would have had no lack of wind to rise upon the air. He seems, if the accounts given be correct, to have exhibited some very remarkable phenomena of "aspiration" which we shall find reproduced in one or two experiments yet to be noticed, and which the soaring birds exhibit every day to the observer, but he was baffled by the lack of fore-and-aft equilibrium.

A History of Aeronautics Ante to Wenham, Stringfellow and the French experimenters already noted, by some years, was Le Bris, a French sea captain, who appears to have required only a thorough scientific training to have rendered him of equal moment in the history of gliding flight with Lilienthal himself. Le Bris, it appears, watched the albatross and deduced, from the manner in which it supported itself in the air, that plane surfaces could be constructed and arranged to support a man in like manner. Octave Chanute, himself a leading exponent of gliding, gives the best description of Le Bris's experiments in a work, Progress in Flying Machines, which, although published as recently as I 1894, is already rare. Chanute draws from a still rarer book, namely, De la Landelle's work published in 1884. Le Bris himself, quoted by De la Landelle as speaking of his first visioning of human flight, describes how he killed an albatross, and then--'I took the wing of the albatross and exposed it to the breeze; and lo! in spite of me it drew forward into the wind; notwithstanding my resistance it tended to rise. Thus I had discovered the secret of the bird! I comprehended the whole mystery of flight.' This apparently took place while at sea; later on Le Bris, returning to France, designed and constructed an artificial albatross of sufficient size to bear his own weight. The fact that he followed the bird outline as closely as he did attests his lack of scientific training for his task, while at the same time the success of the experiment was proof of his genius. The body of his artificial bird, boat-shaped, was 13 1/2 ft. in length, with a breadth of 4 ft. at the widest part. The material was cloth stretched over a wooden framework; in front was a small mast rigged after the manner of a ship's masts to which were attached poles and cords with which Le Bris intended to work the wings. Each wing was 23 ft. in length, giving a total supporting surface of nearly 220 sq. ft.; the weight of the whole apparatus was only 92 pounds. For steering, both vertical and horizontal, a hinged tail was provided, and the leading edge of each wing was made flexible. In construction throughout, and especially in that of the wings, Le Bris adhered as closely as possible to the original albatross. He designed an ingenious kind of mechanism which he termed 'Rotules,' which by means of two levers gave a rotary motion to the front edge of the wings, and also permitted of their adjustment to various angles. The inventor's idea was to stand upright in the body of the contrivance, working the levers and cords with his hands, and with his feet on a pedal by means of which the steering tail was to be worked. He anticipated that, given a strong wind, he could rise into the air after the manner of an albatross, without any need for flapping his wings, and the account of his first experiment forms one of the most interesting incidents in the history of flight. It is related in full in Chanute's work, from which the present account is summarised. Le Bris made his first experiment on a main road near Douarnenez, at Trefeuntec. From his observation of the albatross Le Bris concluded that it was necessary to get some initial velocity in order to make the machine rise; consequently on a Sunday morning, with a breeze of about 12 miles an hour blowing down the road, he had his albatross placed on a cart and set off, with a peasant driver, against the wind. At the outset the machine was fastened to the cart by a rope running through the rails on which the machine rested, and secured by a slip knot on Le Bris's own wrist, so that only a jerk on his part was necessary to loosen the rope and set the machine free. On each side walked an assistant holding the wings, and when a turn of the road brought the machine full into the wind these men were instructed to let go, while the driver increased the pace from a walk to a trot. Le Bris, by pressure on the levers of the machine, raised the front edges of his wings slightly; they took the wind almost instantly to such an extent that the horse, relieved of a great part of the weight he had been drawing, turned his trot into a gallop. Le Bris gave the jerk of the rope that should have unfastened the slip knot, but a concealed nail on the cart caught the rope, so that it failed to run. The lift of the machine was such, however, that it relieved the horse of very nearly the weight of the cart and driver, as well as that of Le Bris and his machine, and in the end the rails of the cart gave way. Le Bris rose in the air, the machine maintaining perfect balance and rising to a height of nearly 300 ft., the total length of the glide being upwards of an eighth of a mile. But at the last moment the rope which had originally fastened the machine to the cart got wound round the driver's body, so that this unfortunate dangled in the air under Le Bris and probably assisted in maintaining the balance of the artificial albatross. Le Bris, congratulating himself on his success, was prepared to enjoy just as long a time in the air as the pressure of the wind would permit, but the howls of the unfortunate driver at the end of the rope beneath him dispelled his dreams; by working his levers he altered the angle of the front wing edges so skilfully as to make a very successful landing indeed for the driver, who, entirely uninjured, disentangled himself from the rope as soon as he touched the ground, and ran off to retrieve his horse and cart. Apparently his release made a difference in the centre of gravity, for Le Bris could not manipulate his levers for further ascent; by skilful manipulation he retarded the descent sufficiently to escape injury to himself; the machine descended at an angle, so that one wing, striking the ground in front of the other, received a certain amount of damage. It may have been on account of the reluctance of this same or another driver that Le Bris chose a different method of launching himself in making a second experiment with his albatross. He chose the edge of a quarry which had been excavated in a depression of the ground; here he assembled his apparatus at the bottom of the quarry, and by means of a rope was hoisted to a height of nearly 100 ft. from the quarry bottom, this rope being attached to a mast which he had erected upon the edge of the depression in which the quarry was situated. Thus hoisted, the albatross was swung to face a strong breeze that blew inland, and Le Bris manipulated his levers to give the front edges of his wings a downward angle, so that only the top surfaces should take the wing pressure. Having got his balance, he obtained a lifting angle of incidence on the wings by means of his levers, and released the hook that secured the machine, gliding off over the quarry. On the glide he met with the inevitable upward current of air that the quarry and the depression in which it was situated caused; this current upset the balance of the machine and flung it to the bottom of the quarry, breaking it to fragments. Le Bris, apparently as intrepid as ingenious, gripped the mast from which his levers were worked, and, springing upward as the machine touched earth, escaped with no more damage than a broken leg. But for the rebound of the levers he would have escaped even this. The interest of these experiments is enhanced by the fact that Le Bris was a seafaring man who conducted them from love of the science which had fired his imagination, and in so doing exhausted his own small means. It was in 1855 that he made these initial attempts, and twelve years passed before his persistence was rewarded by a public subscription made at Brest for the purpose of enabling him to continue his experiments. He built a second albatross, and on the advice of his friends ballasted it for flight instead of travelling in it himself. It was not so successful as the first, probably owing to the lack of human control while in flight; on one of the trials a height of 150 ft. was attained, the glider being secured by a thin rope and held so as to face into the wind. A glide of nearly an eighth of a mile was made with the rope hanging slack, and, at the end of this distance, a rise in the ground modified the force of the wind, whereupon the machine settled down without damage. A further trial in a gusty wind resulted in the complete destruction of this second machine; Le Bris had no more funds, no further subscriptions were likely to materialise, and so the experiments of this first exponent of the art of gliding (save for Besnier and his kind) came to an end. They constituted a notable achievement, and undoubtedly Le Bris deserves a better place than has been accorded him in the ranks of the early experimenters.

|

© Copyright 1999-2002 CTIE - All Rights Reserved - Caution |

Jean-Marie Le Bris

Jean-Marie Le Bris