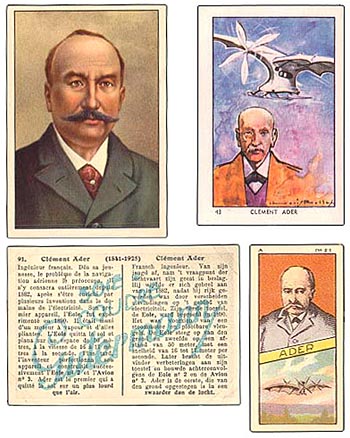

Clément Ader (1841-1926)

Self-taught French engineer and inventor, and a pioneer of flight before the Wright brothers.

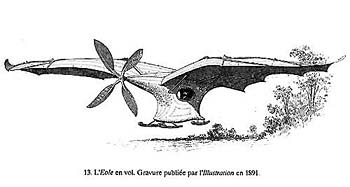

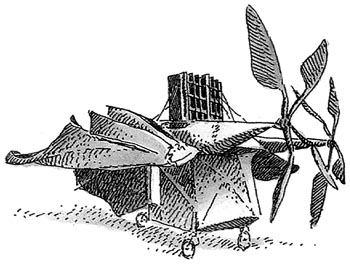

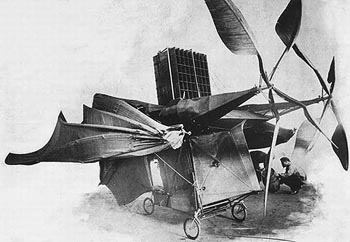

He then focused on the problem of heavier-than-air flying machines and in 1890 built a steam-powered, bat-winged monoplane, which he named the Eole. On October 9 he flew it a distance of 50 m (160 feet) on a friend's estate near Paris. The steam engine was unsuitable for sustained and controlled flight, which required the gasoline engine; nevertheless, Ader's short hop was the first demonstration that a manned heavier-than-air machine could take off from level ground under its own power. Between 1894 and 1897 Clément Ader built a larger but still 'batlike' twin screw machine which he named the Avion (Ed.)

Clément Ader 1841 - 1926

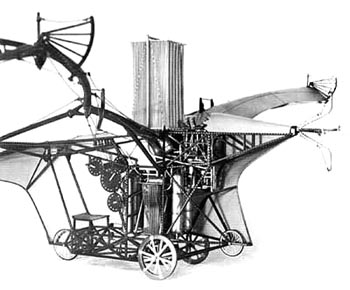

The Eole Clément Ader's 'Eole' in Flight Clément Ader, L'Illustration, 1891 download a larger image

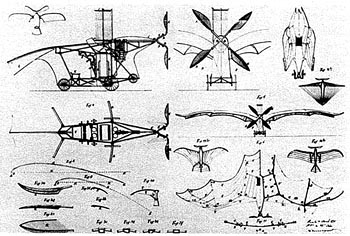

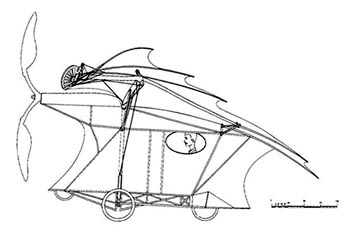

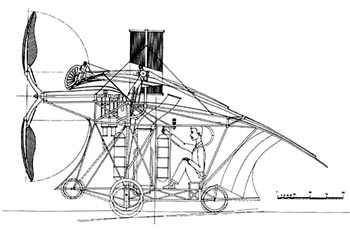

Clément Ader's 'Eole' Patent Drawings download a larger image

Clément Ader's 'Eole', (Front Elevation) download a larger image

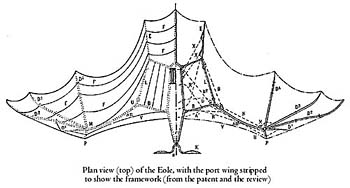

Clément Ader's 'Eole', (Plan) download a larger image

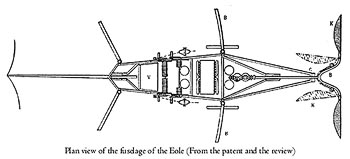

Clément Ader's 'Eole', Fuselage, (Plan) download a larger image

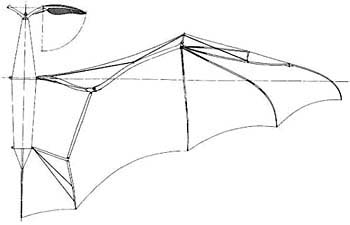

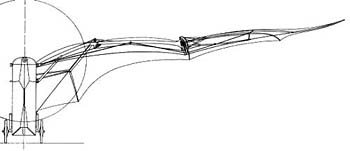

Clément Ader's 'Eole', wing detail, (Plan) download a larger image

Clément Ader's 'Eole', wing detail, (Front Elevation) download a larger image

Clément Ader's 'Eole', (Side Elevation) download a larger image

Clément Ader's Eole, (Side Elevation Alt.) download a larger image

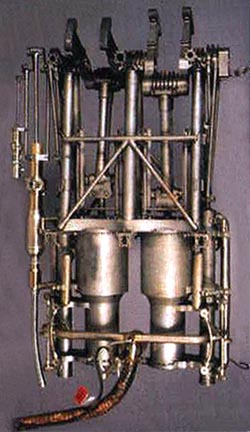

Clément Ader's Eole, Motor download a larger image

Clément Ader's Eole download a larger image

Clément Ader's Eole, Replica download a larger image

Miscellany

Clément Ader, cigarette cards download a larger image

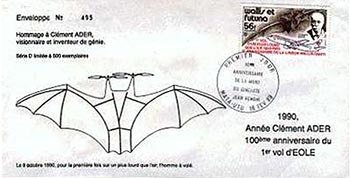

Clément Ader FDC, 1990 download a larger image

Links

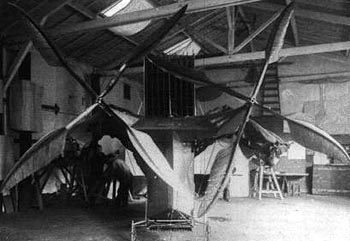

The Avion III Clément Ader's Avion III on display in Paris c.1900 download a larger image

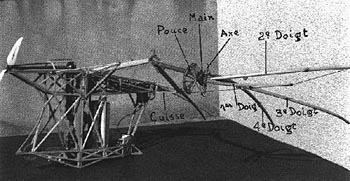

Clément Ader's Avion III, the "Bat" Musée des arts et métiers, La revue No;13, december 1995, pp. 23-31 Clément Ader's Avion III, otherwise known as the "Bat", one of the centrepieces at the Musée des arts et métiers, was restored in the 1980s by the Musée de l'air et de l'espace at its workshop in Meudon, near Paris.

Clément Ader's Avion III in 1895 download a larger image

The aircraft, which has a wingspan of over 15 metres and is equipped with two 20-HP steam engines and two propellors, was built between 1894 and 1897 in Paris, in the rue Jasmin workshop. The materials used were basically wood and, for a small number of parts, steel, brass and aluminium. The web on the wings was made from silk pongee which, in spite of its tight weave, is permeable to air.

Clément Ader's Avion III in 1897 download a larger image

Experiments on the prototype, which required a considerable amount of work, began in October 1897. Interrupted after an accident, the work was not continued due to a lack of financial resources. However, Ader claimed that a 300-metre flight had taken place, a fact confirmed by two witnesses.

Clément Ader's Avion III in 1908

Biruta Kresling was given the opportunity of studying the airplane close at hand when it was 'dissected' - 'taken to pieces', enabling her to find out all the details relating to its manufacture and produce a series of drawings. She was immediately struck by the great intuition shown by Ader in transposing the mechanical principles of bat flight, particularly that of the flying fox.

Clément Ader's Avion III in 1908 download a larger image

With the impression of experiencing a remarkable adventure, Biruta Kresling laid bare the aircraft's design, revealing the astonishingly bionic (before the term was coined) elements which inspired Clément Ader, engineer and prodigious inventor, and examining the new ideas he introduced.

Clément Ader's Eole (construction detail) download a larger image

Although the 'Bat' plane remains virtually unknown outside France, and in spite of the fact that Ader's copy of the natural model (faithful right down to the terms he used - 'arm', 'forearm', 'fingers', 'elbow', 'wood') seems naive and clumsy today, all these technical concepts, for which Ader had no theoretical bases or experimental means at his disposal other than those he used himself (large flying models, a glider, the Eole aircraft and, finally, the life-size plane itself), were extremely advanced for the time.

Clément Ader's Eole (construction detail) download a larger image

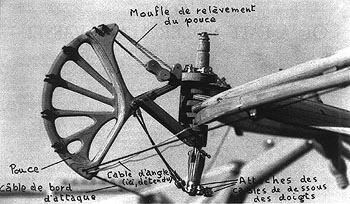

The resemblances between the aircraft and the animal are by no means coincidental. Ader did in fact recommend building the wings of low-speed planes on the model of a bat's wing, and those of high-speed planes on the model of a bird's wing. Among the many similarities between 'Avion III' and the flying fox or birds, we will look at just a few examples. Doubtless aware that the pilot would be unable to steer such a complex aircraft without the assistance of self-stabilizing devices, depending on the shapes and materials used, Ader invented mechanisms such as propeller blades inspired by the quills in birds' wings, made of paper and bamboo - a sort of 'propfan' and blade 'with automatic variable pitch'. The shaft of the propeller blades consisted in a central strand made of cork onto which thin sheets of split bamboo were assembled and stuck. The unit was mounted in such a way as to flatten out at high speeds, automatically regulating the angle of incidence. The 'thumb' of the flying fox combines two functions: firstly, the unfurling and automatic tensing of a membrane similar to the 'leading edge flap' in an aircraft, followed by the folding back of the wing, with the thumb now acting as a hook enabling the bat to grip onto the branch of a tree. The same coupled mechanism - a safety device for the animal - gave Ader's flying machine, designed for military aviation, an essential, dual function: the wing could be tensed and then folded back, meaning that large wing surface areas could be reduced. A single mechanism thus facilitated the processes of putting the aircraft into operation rapidly by unfurling the wings, bringing it to rest, transporting it from the airfield to the hangar, followed by fast, easy removal and dissimulation once it had landed. X-rays of the 'arm' of Avion III showed its hollow inner space to be criss-crossed with thin wooden rods driven into the sides of the tube. These make the arm rigid, similar to the bony trabeculae - the thin rods which reinforce the humerus in birds. As Director of the Musée de l'air et de l'espace, General Pierre Lissarrague supervised restoration work on the plane. He began by carrying out a critical study of the countless technical notes in Clément Ader's workshop notebooks. In order to check that Ader's ribless wing did indeed have the hollow profile announced in the patent, Lissarrague came up with the idea of testing an original half-wing from the plane, with its 'arm-bones' and 'fingers', covering it with a new layer of silk pongee, just like the one on the original wing which was used as a model, and exposing it to natural wind. The experiment took place outdoors, on the west coast of the Cottentin peninsula. The 'automatic ' curve of the thin 'fingers' and the membrane of the aircraft could thus be observed in simulated flight, as could the profiles along its wingspan. The placing of reflective strips under the wing enabled the shape of these profiles to be photographed, while measuring the way in which they are positioned in relation to one another. © Musée des arts et métiers - O.D. - 6/04/98

A History of Aeronautics

Part IX. Not Proven : Ader The early history of flying, like that of most sciences, is replete with tragedies; in addition to these it contains one mystery concerning Clément Ader, who was well known among European pioneers in the development of the telephone, and first turned his attention to the problems of mechanical flight in 1872. At the outset he favoured the ornithopter principle, constructing a machine in the form of a bird with a wing-spread of twenty-six feet; this, according to Ader's conception, was to fly through the efforts of the operator. The result of such an attempt was past question and naturally the machine never left the ground. A pause of nineteen years ensued, and then in 1886 Ader turned his mind to the development of the aeroplane, constructing a machine of bat-like form with a wingspread of about forty-six feet, a weight of eleven hundred pounds, and a steam-power plant of between twenty and thirty horse-power driving a four-bladed tractor screw. On October 9th, 1890, the first trials of this machine were made, and it was alleged to have flown a distance of one hundred and sixty-four feet. Whatever truth there may be in the allegation, the machine was wrecked through deficient equilibrium at the end of the trial. Ader repeated the construction, and on October 14th, 1897, tried out his third machine at the military establishment at Satory in the presence of the French military authorities, on a circular track specially prepared for the experiment. Ader and his friends alleged that a flight of nearly a thousand feet was made; again the machine was wrecked at the end of the trial, and there Ader's practical work may be said to have ended, since no more funds were forthcoming for the subsidy of experiments. There is the bald narrative, but it is worthy of some amplification. If Ader actually did what he claimed, then the position which the Wright Brothers hold as first to navigate the air in a power-driven plane is nullified. Although at this time of writing it is not a quarter of a century since Ader's experiment in the presence of witnesses competent to judge on his accomplishment, there is no proof either way, and whether he was or was not the first man to fly remains a mystery in the story of the conquest of the air. The full story of Ader's work reveals a persistence and determination to solve the problem that faced him which was equal to that of Lilienthal. He began by penetrating into the interior of Algeria after having disguised himself as an Arab, and there he spent some months in studying flight as practiced by the vultures of the district. Returning to France in 1886 he began to construct the 'Eole,' modelling it, not on the vulture, but in the shape of a bat. Like the Lilienthal and Pilcher gliders this machine was fitted with wings which could be folded; the first flight made, as already noted, on October 9th, 1890, took place in the grounds of the chateau d'Amainvilliers, near Bretz; two fellow-enthusiasts named Espinosa and Vallier stated that a flight was actually made; no statement in the history of aeronautics has been subject of so much question, and the claim remains unproved. It was in September of 1891 that Ader, by permission of the Minister of War, moved the 'Eole' to the military establishment at Satory for the purpose of further trial. By this time, whether he had flown or not, his nineteen years of work in connection with the problems attendant on mechanical flight had attracted so much attention that henceforth his work was subject to the approval of the military authorities, for already it was recognised that an efficient flying machine would confer an inestimable advantage on the power that possessed it in the event of war. At Satory the 'Eole' was alleged to have made a flight of 109 yards, or, according to another account, 164 feet, as stated above, in the trial in which the machine wrecked itself through colliding with some carts which had been placed near the track--the root cause of this accident, however, was given as deficient equilibrium. Whatever the sceptics may say, there is reason for belief in the accomplishment of actual flight by Ader with his first machine in the fact that, after the inevitable official delay of some months, the French War Ministry granted funds for further experiment. Ader named his second machine, which he began to build in May, 1892, the 'Avion,' and--an honour which he well deserve--that name remains in French aeronautics as descriptive of the power-driven aeroplane up to this day. This second machine, however, was not a success, and it was not until 1897 that the second 'Avion,' which was the third power-driven aeroplane of Ader's construction, was ready for trial. This was fitted with two steam motors of twenty horse-power each, driving two four-bladed propellers; the wings warped automatically: that is to say, if it were necessary to raise the trailing edge of one wing on the turn, the trailing edge of the opposite wing was also lowered by the same movement; an under-carriage was also fitted, the machine running on three small wheels, and levers controlled by the feet of the aviator actuated the movement of the tail planes.

Clément Ader's Avion III download a larger image

On October the 12th, 1897, the first trials of this 'Avion' were made in the presence of General Mensier, who admitted that the machine made several hops above the ground, but did not consider the performance as one of actual flight. The result was so encouraging, in spite of the partial failure, that, two days later, General Mensier, accompanied by General Grillon, a certain Lieutenant Binet, and two civilians named respectively Sarrau and Leaute, attended for the purpose of giving the machine an official trial, over which the great controversy regarding Ader's success or otherwise may be said to have arisen. We will take first Ader's own statement as set out in a very competent account of his work published in Paris in 1910. Here are Ader's own words:

'After some turns of the propellers, and after travelling a few metres, we started off at a lively pace; the pressure-gauge registered about seven atmospheres; almost immediately the vibrations of the rear wheel ceased; a little later we only experienced those of the front wheels at intervals. 'Unhappily, the wind became suddenly strong, and we had some difficulty in keeping the "Avion" on the white line. We increased the pressure to between eight and nine atmospheres, and immediately the speed increased considerably, and the vibrations of the wheels were no longer sensible; we were at that moment at the point marked G in the sketch; the "Avion" then found itself freely supported by its wings; under the impulse of the wind it continually tended to go outside the (prepared) area to the right, in spite of the action of the rudder. On reaching the point V it found itself in a very critical position; the wind blew strongly and across the direction of the white line which it ought to follow; the machine then, although still going forward, drifted quickly out of the area; we immediately put over the rudder to the left as far as it would go; at the same time increasing the pressure still more, in order to try to regain the course. The "Avion" obeyed, recovered a little, and remained for some seconds headed towards its intended course, but it could not struggle against the wind; instead of going back, on the contrary it drifted farther and farther away. And ill-luck had it that the drift took the direction towards part of the School of Musketry, which was guarded by posts and barriers. Frightened at the prospect of breaking ourselves against these obstacles, surprised at seeing the earth getting farther away from under the "Avion," and very much impressed by seeing it rushing sideways at a sickening speed, instinctively we stopped everything. What passed through our thoughts at this moment which threatened a tragic turn would be difficult to set down. All at once came a great shock, splintering, a heavy concussion: we had landed.'Thus speaks the inventor; the cold official mind gives out a different account, crediting the 'Avion' with merely a few hops, and to-day, among those who consider the problem at all, there is a little group which persists in asserting that to Ader belongs the credit of the first power-driven flight, while a larger group is equally persistent in stating that, save for a few ineffectual hops, all three wheels of the machine never left the ground. It is past question that the 'Avion' was capable of power-driven flight; whether it achieved it or no remains an unsettled problem. Ader's work is negative proof of the value of such experiments as Lilienthal, Pilcher, Chanute, and Montgomery conducted; these four set to work to master the eccentricities of the air before attempting to use it as a supporting medium for continuous flight under power; Ader attacked the problem from the other end; like many other experimenters he regarded the air as a stable fluid capable of giving such support to his machine as still water might give to a fish, and he reckoned that he had only to produce the machine in order to achieve flight. The wrecked 'Avion' and the refusal of the French War Ministry to grant any more funds for further experiment are sufficient evidence of the need for working along the lines taken by the pioneers of gliding rather than on those which Ader himself adopted.

Clément Ader's Avion III download a larger image

Let it not be thought that in this comment there is any desire to derogate from the position which Ader should occupy in any study of the pioneers of aeronautical enterprise. If he failed, he failed magnificently, and if he succeeded, then the student of aeronautics does him an injustice and confers on the Brothers Wright an honour which, in spite of the value of their work, they do not deserve. There was one earlier than Ader, Alphonse Penaud, who, in the face of a lesser disappointment than that which Ader must have felt in gazing on the wreckage of his machine, committed suicide; Ader himself, rendered unable to do more, remained content with his achievement, and with the knowledge that he had played a good part in the long search which must eventually end in triumph. Whatever the world might say, he himself was certain that he had achieved flight. This, for him, was perforce enough.

Clément Ader's Avion III on display today download a larger image Photo: Frédéric Boulanger http://wwwsi.supelec.fr/fb/Personnel.html

|

© Copyright 1999-2002 CTIE - All Rights Reserved - Caution |